Archive for the ‘Markets’ Category

Often on Wall Street and in the media, the worst thing you can do for your career is not have an opinion. When I in training at Citi, they told us “no matter what have an opinion”. This is, of course, because conviction sells.

This need to have a view is best displayed in the Economic and Macro arena, where economists and analysts come together for something resembling the combination of a circle jerk and a pissing match. Currently there is a big inflation/deflation debate reverberating through the markets and media. This is an important debate and the side of the debate you are on will dramatically affect the composition of your portfolio. But what if you’re just not sure?

It’s ok to not be sure. I have no idea where we are headed and I don’t think I’m alone. Even the pros these days trading global macro strategies are having a hard time. Never (in my somewhat limited experience) have a seen such a bipolar market.

This can be visualized in the chart of the $ES_F.

The flash crash as well as the volatile range through the flash crash candle since May seems to indicate market participants who are both unsure and fearful of being wrong.

So what do you do when you don’t know?

Don’t Invest

One option is to get out of the market when you’re unsure. Joe Fahmy (@jfahmy) has no problem doing this. He often says if a market is not healthy, he doesn’t want to be in it.

This can have high portfolio turnover but portfolio benefits (and health benefits) can offset those costs. If you are actively investing in a market that you’re unsure of you’re more susceptible to mistakes and cognitive biases. Not to mention stress eats you alive.

Invest in Both

One investment strategy that Taleb mentions in The Black Swan is to investing most of your money in T-bills and then putting a small percentage to take advantage of highly improbable events with asymmetric returns. If you believe we’re going to move big, whether there be inflation or deflation you can bet on both. If you structure a portfolio such that the return on one will outweigh the loss on the other, you can literally invest in your “I don’t know” thesis.

Perhaps the much-talked about strength in bonds is a sign that people are doing this, whether investors are aware of their uncertainty or not.

For some ideas on how to play both sides see these posts on Inflation and Deflation by @marketfolly as well as this one over at Pragmatic Capitalist.

Play From the Bottom Up

If you’re having trouble investing from a top-down perspective, perhaps you may want to look from the bottom-up. Tadas Viskanta over at Abnormal Returns has been talking about the forthcoming Golden Age of Stock-Picking. Even in an uncertain economic world, there will always be secular trends to emerge and invest in. The recent strength in names such as $AMZN, $NFLX, and $GMCR shows that secular growth is trading at a premium.

Peter Lynch is famous for remarking, “Invest in what you know.” Even if what you know is that you don’t know, there are still ways to invest.

I’m a sucker for Google Trends. Ever since it first came out, I’ve loved to have fun with it.

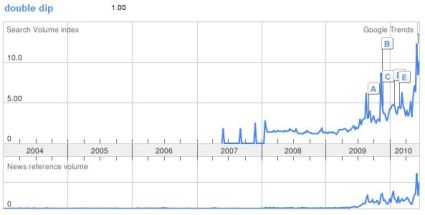

Recently, I’ve noticed the word “double dip” seriously infiltrate the collective vocabulary and wondered what Google Trends had to say about it. My suspicions were correct, as we’ve seen a massive spike in search traffic and news reference regarding this recently:

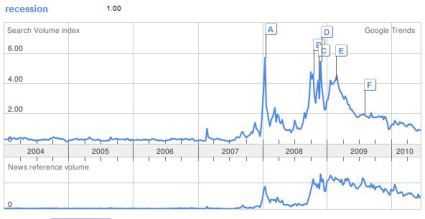

Compare this to the chart for “recession” during late-2007. Similar spike on search volume and news reference:

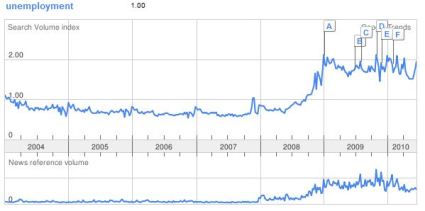

Couple this with a nice spike in “unemployment” (which has been a pretty decent reliable indicator) and things look pretty bleak.

In some instances, searches are a great contrary indicator, such as for investments (look at the 2008 spike for Gold as an example). For economic related searches they are many times leading. Look at the spike for “recession” in late 2007. While things were a bit rocky then, we weren’t in the throes in the recession. In fact, the Google Trend for “recession” had stabilized by the time the recession ended. Since Google Searches are conducted by real people, when nobody is watching, I believe they are a great look into the mindset of the average individual, and right now appear to be painting a bit of a scary picture.

Yesterday, I came across a post by Jason Zweig on the Intelligent Investor blog. The post basically outlines how humans are hardwired to herd, and thus we see it quite often in the financial markets. This isn’t news to any student of the market and I agree completely.

I disagree, however, with the conclusion that he makes:

Thus, if you buy individual stocks, you should note which way the herd is moving—and go the other way. You should get interested in a stock when its price gets trampled flat by investors stampeding out of it. The list of new 52-week lows is a rough guide to what the voting machine has been trashing lately. Then run your own weighing machine, studying the company’s financial statements, products and competitors to determine the value of its business—while ignoring the current price of its stock. And make a permanent record that thoroughly details your rationale for making the investment. That way, you set in stone exactly where you stood before the herd began trying to sweep you away.

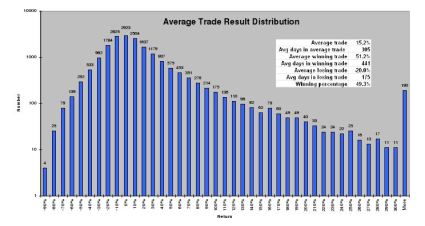

In my opinion this advice in dealing with the herd is far too simplistic. Betting against the herd can be quite profitable at times, but can be disastrous other times. In fact, buying stocks at all time highs has a very attractive return distribution according to an interesting paper by Black Star Funds, Does Trend Following Work on Stocks:

Sean Park, a former trader and now an early stage financial technology investor often describes his investing strategy as “Skate Where the Puck Is Going To Be”. I think this conclusion better fits the natural herding behavior in markets. In markets, at all times you want to be in front of the herds next move. As trends can often times persist, some times this involves a position amongst the herd with healthy skepticism of the underlying fundamentals and belief system of the pack. Herds can quickly become mobs and trends can reverse sharply, thus other times a position in opposition of the herd is prudent with an awareness that you may be stepping in front of a stampede.

Investors must be aware of the state of the herd, the fundamental dynamics underlying both the herd and the counter-herd, and craft an investment strategy that takes advantage of the herds next move, not that herds are often times wrong.

“If you don’t like what I have to write go start a blog that no one will read”

-Anonymous

There has been a good amount of hatred of Business Insider out there lately. The latest, coming from 1938 Media is brutal:

While I agree with him that a business journalist should know who Peter Drucker is, or at the very least spend five minutes on Wikipedia researching him, his other complaints are nothing new.

Between the slideshows, ridiculous stories, and outrageous headlines, it’s easy to poke fun at Business Insider. Whenever I hear a lot of haters come out on a new company or new product, I tend to get interested in what they’re doing, because it means they’re being disruptive. There are many posts,tweets, and (now) videos laying out the anti-Business Insider Case, but many of these complaints are the side effect of disruption (and a good deal come from some of the people who are being disrupted).

Let’s look at some of these complaints through the lens of disruption and look at some of the things Business Insider is doing right.

They’re Hacking a Broken System…and That’s Good

It’s no secret that Business Insider is on ruthless quest for page views though their use of slideshows and ridiculous stories. This transparency and “no-shame” approach causes many to attack the company itself, rather than the industry at larger. Many are hating the player, instead of the game.

Like it or not, the online media business is a market for page vies. Content companies must go out mine as many page views as possible, and sell them to advertisers. While one can opine about the CPM model until the cows come home (and I for one am not a fan), that is the system, and Business Insider is simply hacking it.

Many times a hacker in a system exposes its weaknesses and helps improve it. Those who chide Business Insider for doing this are missing the point – Business Insider could be responsible for the downfall of the CPM model. As advertisers wise up to the fact that the system is broken and other sites begin to mimic Business Insider’s behavior (slidehows are starting to spread!), the system will have to change, and this is a good thing. By shamelessly exposing the stupidity of the CPM model, Business Insider unfortunately becomes the poster child for this model, but in reality they could potentially be a major force in disrupting it.

“Scraping” Benefits the Consumer of News

A common complaint about Business Insider, and other aggregators, is that they are “scraping the web”, but from the POV of the consumer is that really a bad thing?

Would you say that the person who has to buy his groceries at 10 different specialized stores or at one supermarket is better off? Those that argue against “scraping” are basically saying that the consumer benefits from having to run around and buy at 10 different locations. The centralized marketplace definitely hurts the margins of the individual food distributors but transfers benefits to the consumer. The Business Insider model, (and many aggregator/curator models) is as a centralized marketplace for news.

At this marketplace I find a ton of lesser known stories that I wouldn’t find on my own. Increasingly , the blogosphere is the tail that wags the dog for the mainstream media and they are making that information available to the mass markets. Two or three years ago, unless you were a geek with a Google Reader account and a ton of curiosity, you wouldn’t access some of these writers, sites, and ideas. While some news producers many not like this, I can’t see how this is a bad thing for the news consumer.

Plus this is nothing new. It was the major media outlets that first started “scraping” each others stories. In a great podcast on the state of media, Dan Carlin points out that the major media outlets stopped “owning the story” years ago. Whats the difference between Brian Williams on the evening news saying “According to ABC News…” and then reporting the exact story that ABC broke and what Business Insider does? Where is the Brian Williams outrage? He doesn’t even link to their broadcast! At least Business Insider does that! The reality is that nobody owns the story anymore, and as long as that cat is out of the bag you can’t single out Business Insider as some sort of rogue rule-breaker.

They Understand Twitter and the Social Web More than Anyone Else in the Media

Most of the Business Insider staff are in their 20’s or 30’s. The company is really one of the first media outlets composed entirely of a generation of people who grew up on the web. Because of this they have a deep understanding of the new distribution channels the it creates.

Many people’s social media strategies fail because they don’t communicate on the web the same way they would at a party or social gathering. Older people whose physical life was interrupted by the digital revolution see a more difference between physical communities and digital ones than their younger counterparts. Those that have grown up on the web see very little difference at all because they don’t really know a physical world without a digital world. On the social web, people share the same type of information that they share in real life. Those that understand this natural tendency can transform their readers to a major distribution outlet. Business Insiders young workforce understands this by nature.

In the physical world when you are hanging out with your friends you usually share interesting, sometimes absurd news. For whatever reason socially, it is a great conversation starter. When meeting with friends in the physical world its not uncommon for someone to say, “Did you hear about the guy who runs through Grand Central station naked every day?”. Why would this be any different on the web? Business Insider publishes some outrageous content, but in doing so they give you something to talk about, and in doing so turn you into distribution for their content. They know what people like to share online, because online sharing is in their DNA.

Business Insider = Paperboys 2.0

Remember the iconic picture of the paperboy on the street yelling “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!”? Paperboys were news salesmen. They would shout out interesting articles or stories in the paper, many times adding hyperbole to the actually story. By writing enticing headlines, parsing a story to find interesting tidbits, and getting the word out on Twitter first, Business Insider is the paperboy of online content.

As I mentioned earlier, they are a centralized marketplace for news and they are selling content better than most content creators themselves. The competition for eyeballs is fierce online and I don’t see how having a sales force like them working for you is a bad thing. Sure they take a “commission” in the form of page views, but in a time when content producers are having a hard time selling news why not do business with the marketplace with the strongest marketing arm?

This whole experiment could certainly fail and the Business Insider approach has some negative qualities, such as perhaps perpetuating what I like to call the “disease of the absurd” afflicting media, but Business Insider is doing a ton of innovative and interesting things some of which could positively benefit the news industry as a whole. They are hacking the system and in doing so they will change it – I think mostly for the better.

Two big types of feedback we get at StockTwits :

1) There is a lot of noise on StockTwits

2) There needs to be a way to track performance and/or rate traders.

While we take all feedback very seriously both are valid and we are constantly building tools to filter and use the data and discover new traders, both miss the point of what StockTwits truly is – the second derivative of market data.

StockTwits is market data with a semantic layer on top. It is a centralized stream of information and ideas consisting of decentralized analysis. Using this context let’s address the points above:

Regular Market Data is Noisy

StockTwits is data and information, so of course there is noise. Market data is mostly noise so why wouldn’t the second derivative of market data consist of noise as well. Standard market data is an older and more established form of noise that has been around for a while and already has the tools to filter and analyze it so people don’t see it that way. Most of the daily ticks, trades during the day are immensely noisy, yet people pay top dollar for this data and extract alpha from it. Our job is to build tools and enable others to build tools to be able to transform and use this new second derivative of market data.

Noise is Relevant

Real time data is very contextual and real time which adds to the noise factor for someone who isn’t there. Just like “you had to be there to get the joke” you have to be on StockTwits to understand the information coming through. The more time you spend the more signal there is.

StockTwits is Work

Anyone who has spent any time investing or trading know that its work and a full time job. Whatever your strategy is there is a lot of time conducting and reading research, testing models and looking for ideas. I fear that many people think that StockTwits is the “easy”. It’s not. Nothing in the market it easy. StockTwits is the second derivative of market data. It’s market data refined to a usable form. Just like there is a lot of work needed to take refined oil and make your car run successfully, there is work that needs to be done to take this refined data and ideas and put them to work in your portfolio.

As a student of the stream, I know that certain traders are better in certain markets. I know that @wwwstockrake awesome in markets that are volatile and turning (like this one). I also know that swing traders like @zortrades and @traderstewie are better in trending markets. I know to discount information from them depending on the type of market you are in. This is something that I have picked up after spending time watching StockTwits.

Just as a portfolio puts in work to calculate the information ratio on the stocks in his portfolio, someone using StockTwits must do the same. Using StockTwits information may be a bit easier and different, but it is still work.

There is Nothing More Transparent than a Someone’s Stream

This week a very respected and uber-transparent trader in our community, @johnwelshphd, proposed a ratings system for traders. He’s not the first to have this suggestion and we’ve had many people request performance for traders, and while perhaps in the future we may implement something along the lines, there is nothing more valuable and transparent than a user’s stream.

There is nothing more transparent than someone’s StockTwits stream. If someone only tweets exits it takes only a minute of reading their stream to see this. If someone never tweets losing trades it only takes a few minutes to see that. Any rating system can be gamed. Sites like Investimonials, while a great idea and somewhat useful are getting gamed hard. Heck, the ratings agencies that are the backbone of the debt markets were gamed hard (and contributed to the fall). Gamed ratings systems obscure reality and sometimes create false realities. Often times less is more, and there is nothing more transparent than a user’s stream.

Plus, ratings systems shifts the focus away from the ideas and information and towards the trader themselves. New and even bad traders can sometimes have great ideas, and vice versa. The great thing about golf is that even the worst golfer can often times hit a shot like a pro. Focusing on the individuals is what CNBC and the mainstream media do. Each day they trot on a hedge fund or mutual fund manager who is a better salesman than investor who goes on and talks their book. In the investment world, celebrity brings liquidity and the guru becomes a self fulfilling prophecy. Focusing on the idea and not the individual is much more democratic and disruptive.

Tom Brakke writes in Cave and the Flow:

These days, it is not hard to be pulled into the flow of information. Digital devices bring it to wherever we may be, at all hours of the day or night. The flow is a raging river that sweeps us along.

The question is whether or when or how often to seek higher ground and retreat to a cave of our own.

As someone whose mission is to create original ideas, I know that I will do my best work when I spend a lot of time in the cave. But I must also heed the lessons of the river, so I need to gaze down upon it to gauge its features, to approach it close enough to hear the roars of the raging waters, to reach down into it for a handful of water to taste, and sometimes to take a dip in an eddy of information. And yes, occasionally I need to swim out into the main current, hoping that it doesn’t sweep me into raging rapids of confusion or over a waterfall of wasted time.

StockTwits is a place where various market participants come out of their caves and add ideas to the flow. In addition, for those willing to work, it can provide great fodder for those who are going back to their cave to perform analysis. It’s our job to foster the building of tools to make this process better.

I’ve always said that people come online mostly to do variations of two things – talk and play. Today, Matthew Ingram had a great post on GigaOm titled “Why Everything Is Becoming a Game.”

The gist of the post was that a generation of gamers are getting older and that being able to adapt games wisely is becoming a winning strategy. Matthew writes:

What is the impact of all that gaming on our society? One academic, Lee Sheldon of Indiana University, says the generation that has grown up with ubiquitous online gaming is bringing that culture with it into the educational system — and ultimately, into the workforce. “As the gamer generation moves into the mainstream workforce, they are willing and eager to apply the culture and learning techniques they bring with them from games,” Sheldon, an assistant professor at the university’s department of telecommunications, told ITNews. He said older managers will have to “figure out how to educate themselves to the gamer culture, and how to speak to it most effectively.”

He goes on to give examples of companies who have used games effectively such as Slashdot and Wikipedia. He believes games are successful because they take advantage of peoples “innate desire to compete with one another”. I agree.

One such “game” I have been playing lately is a music discovery site, thesixtyone. thesixtyone is a beautifully designed site whose goal is to help users identify great music and bring it to the attention of other users. The game underlying the site is very market-based. You get a fixed amount of hearts that you can give to songs. A heart is like currency that you invest in songs. If you heart a song that other people heart, you earn reputation points. Essentially the investment throws off some return. The more reputation points you earn the more control you have within the economy. This control includes bid to revive songs, which puts a song on the “home” page (which in market terms gives your song a massive amount of attention and “liquidity”). If you run out of hearts you can earn them by listening to really “illiquid” new or unheard of songs, or going on various quests that nudge you to explore music. It’s really a fascinating site.

What I find most interesting about such a site is the game underlying the site forces you to do work. Any audiophile knows that listening to music can be quite rewarding. As most rewarding things, however, it involves a decent amount of work. Pop music is very easy to consume but often times not as complex and rewarding in the long term. Most people don’t want to do the work to discover and find great music but someone has to do it. What the thesixtyone does, is turn that work into a game. Through many of its quests to earn the currency within its economy, it makes you go through the process of discovering and listening to music – and makes it fun and addictive at the same time. It is essentially a market that is designed to allocate the best songs to the most amount of ears. Awesome!

As I said earlier, people come onto the web to mostly to talk and to play – not work. For the next phase of web to really take off a lot of work must be done. A lot of people hate on foursquare but they quite brilliantly use a simple game to get users to do something they ordinarily wouldn’t – share their location. This is work to most people but foursquare has turned it into a game.

We don’t have the algorithms yet to automate things like curation as many algorithms can be gamed too easily. I really think games (and markets) are going to be critical in order to organize and optimize all the information on the web. There is a global web workforce eager to add a curated filter to the web, but I’m afraid the only way to get them do to the heavy-lifting is to get them playing.

Yesterday, The Epicurean Dealmaker penned an excellent piece laying out his “poacher turned gameskeeper” theory on financial regulatory reform. The heart of the “poacher turned gameskeeper” theory is belief that in order to regulate investment banks, you need investment bankers (and you need to pay them banker wages).

He writes,

Now Dick Fuld, at least in his prime, was a forceful and scary man. It takes a certain kind of personality to tell such a man to go fuck himself to his face. Fortunately, we just happen to have a substantial supply of brass-balled, take-no-prisoners, kill-’em-all-and-let-God-sort-’em-out people ready to hand. By happy coincidence, these individuals also happen to be intimately familiar with the ins and outs of the global financial system, the nature and construction of the myriad securities and engineered products polluting financial markets, and the numberless tricks and stratagems large financial institutions use to end-run rules and regulations designed to keep them in check.

These people are called investment bankers.

That’s right, boys and girls: It’s time for the chickens to band together and hire themselves some foxes to guard the chicken coop.

At the end of his post he alludes to the many naysayers who say “it could never happen” and concedes that perhaps they are correct. To this I would say the U.S. Government has already done this in some respect in protecting its information system, so why not it’s financial system.

Last year, it was announced that the U.S. government was looking to hackers to help protect its cyber networks.

From USA Today,

Buffeted by millions of digital scans and attacks each day, federal authorities are looking for hackers — not to prosecute them, but to pay them to secure the nation’s networks.

General Dynamics Information Technology put out an ad last month on behalf of the Homeland Security Department seeking someone who could “think like the bad guy.” Applicants, it said, must understand hackers’ tools and tactics and be able to analyze Internet traffic and identify vulnerabilities in the federal systems.

The rationale behind hiring hackers and paying them to change the color of their hat from black to white is the same rationale that TED uses to hire investment bankers to regulate and protect the system.

Can the financial system be “hacked”. Leigh Caldwell thinks so. In his piece, “Why Can Finance be Hacked?” he writes, “the finance market has nearly all the characteristics of an insecure, unstable, hackable multi-user computer”

And, thus aren’t bankers similar to hackers? The regulators lay out a set of rules of the system and the bankers seek to “hack” the system to their advantage. Who better design and regulate the system then the hackers themselves? You pay them enough to change teams and we might end up with a financial system that is more secure. We are already doing this with the system that protects our national data, why would it be so radical to do it system that protects our national wealth.

Besides, aren’t both really just bits and bytes of information?

As the Volcker Plan limps through Washington and many are screaming bloody Armageddon, an idea has been floating through my head. This is an idea that is sure to really rile up those on Wall Street, many readers of this blog, and followers on Twitter. It is an idea that at the onset seems ridiculous but after pondering for some time has some merit. This idea is nationalizing market-making in vanilla financial instruments.

Liquidity is to the flow of capital as as roads are to the flow of traffic. Most would argue that both the flow of capital and the flow of traffic are both vital to economic well-being. Yet unlike in transportation, in markets we largely leave our market infrastructure up to the private sector. While provision of transportation infrastructure would not pass the public policy test of a pure public good, many would agree that is important and government has a inherent interest in making sure that traffic flows. Why not leave this role up to the government in the capital markets?

Below are some reasons why this idea keeps banging through my head:

Additional Tools for Policy Makers

Over the past 20 years we have experience multiple liquidity crises where the Fed has had to step in and provide liquidity to financial institutions so that they could turn around and use that money to get the markets moving again – aka make markets. The government is already somewhat on the hook as a “liquidity provider of last resort” to the markets, so why not do it all the time.

Think about the additional tools it would give policy makers. Markets getting bubbly? Increase your spreads. Capital not moving? Decreae your spreads. Too much debt being issued? Shift market making capital to equities. Want to create the incentive for Alternative Energy companies? Make liquid markets in their debt and equity. The private sector would never do this. They make markets in wherever it is most profitable at the time. Sometimes to aid other businesses that they are in and can get out of the game in a moments notice.

Steve Waldman at Interfluidity writes that Information is Stimulus:

A housing boom, any kind of boom, is attended by an increase in certainty. Information is stimulus, confusion is contraction. A bust occurs when the market is unsure of everything, when market participants perceive better risk-adjusted return in holding government securities (or supply-inelastic commodities) than in financing real investment. Sectoral shifts per se have no clear implication with respect to variables like employment and output. But “hangovers” do happen, because powerful booms are periods when market participants make consequential decisions with great swagger and confidence, and busts are when we learn that despite their certainty, they were wrong. They are left not only impoverished and burdened by debt, but bereft of confidence in their ability to evaluate new opportunities. The best way to avoid the hangover is not to err so terribly in the first place. Easier said than done, perhaps, but that’s no reason to cop out. We can build a better financial system, one in which degrees of certainty are attached and removed from economic propositions dexterously, rather than clinging like giddy leeches until a collapse.

Nationalizing market making gives policy makers a really interesting way to receive information from and inject information into the markets. I take Waldman’s premise further and say that Capital flows towards information. Under a lens of uncertainty, capital doesn’t flow, but if capital knows that there is a liquidity provider out there with an interest in allowing it to flow, it can flow more smoothly. Nowhere can this seen better than the capital flow to arbitrage strategies, the “sure” thing.

Ability to Put Financial Innovation to Good Use

The last decade of financial innovation in the form of financial engineering should be used to improve market microstructure not allow a few rich people to profit. Staying with the transportation metaphor, engineering breakthroughs such as bridges and roads weren’t built for a few rich people to benefit, but for society as a whole to improve. These financial innovations should be applied in the same way. We should take these brilliant minds, have them build robust, fair market making algorithms, and embed them in our market microstructure so that they benefit society as a whole.

Bid-Ask Spread is Already a Liquidity Tax

The market maker spread is essentially a tax on liquidity. The market-maker provides liquidity and for doing so collects the spread. On top of this brokers get their share in the market. In addition, many are throwing around the idea of a Tobin Tax on top of this. Why not just simplify things and allow the government to simply collect the bid ask spread – a liquidity tax and in return be a stable liquidity provider.

While there are obviously concerns I have with such an idea, such as regulatory capture and inefficiency of the government to operate, the more I think about it, the more it makes sense. I also know that this is something that would never go through in lifetime. In any case, this has been something that I have been ruminating on for some time, not going any further in my own head, and wanted to share it with the blogosphere to see what they think.

Now, please, tear it shreds!

Today I read a piece about how the US Postal Service is looking to cut costs as they stare at a potential cumulative $250 Billion shortfall in 2020.

From Reuters:

The U.S. Postal Service, faced with less mail and bigger shortfalls, plans to cut Saturday delivery and overtime, raise prices and trim its workforce by about 30,000, its chief financial officer, Joseph Corbett, said on Tuesday.

Because of e-mail and private delivery companies, traditional mail volume is expected to be down from last year by about 10 billion pieces in 2010 with first class mail expected to drop 37 percent by 2020, leaving the service with a cumulative shortfall that could hit $238 billion by 2020.

Faced with that shortfall, Corbett said the service was planning a moderate increase in stamp prices and pressing for a law to be changed that would allow it to drop Saturday delivery.

In today’s mailbox, out of 10 -12 pieces I received, only one was actually somewhat important. I would figure most Americans have a similar experience. While this article says that the problem is due to mail volume is dropping, I think the problem is completely the opposite. There is WAY too much mail.

The US Postal Service is setting a price for mail at which the supply dramatically outweighs the demand. This has led to the proliferation of Sharper Image catalogs and Super-Saver coupon packs. It allows many companies to lay off some of their spamming marketing costs onto the post office. The original intention of the post office wasn’t to give horny old men cheap thrills twice a month when the Victoria’s Secret catalog arrived, but to deliver important, relevant messages. Even if I’m wrong, the internet is killing that intention too!

Since the postal service could essentially become a government subsidized spam factory, is this even a business we want to be in? There must be a better and cheaper way to work alongside the private market to ensure that vitally important messages are promptly delivered to the citizens at a reasonable cost.

This week, the Obama Administration turned their attention away from healthcare and towards the banks, announcing the Volcker Plan. While the official plan hasn’t yet been released, the blog and tweetosphere have been buzzing over the last few days. The reactions have ranged from angry to confused.

I figured I would share a few of my thoughts:

- It will be very difficult to define what prop trading is. Two great pieces that illustrate this point are Kid Dynamite and Bronte Capital. That does not mean that it can’t be intelligently done, but it will be difficult (and unlikely). This issue is not simple and those saying it is on either side are wrong.

- This is political but the ends can still justify the means. While this is obviously a political reaction. it doesn’t mean that it should be completely ignored and written off. Let’s be honest here, EVERYTHING that comes out of Washington is political. Many people who were criticizing Obama for not putting forth financial reform are now criticizing Obama because he did. Yes, what he is proposing is not the solution, but criticize the idea not the man. If there is one thing that both sides of the aisle can agree on is that there needs to be some financial reform of some sort. The masses will be happy with something, so it should be in the interest of all incumbents to come together and pass something good. I don’t agree with Obama on many issues, but still would like to see him pass some meaningful financial reform. We must be constructive in how we approach this, not destructive. Use this as a launching pad.

- Just because prop trading didn’t cause the financial crisis doesn’t mean it can’t. A popular argument against the proposed reform is that it doesn’t address the causes of this crisis. This is absolutely true. This crisis wasn’t caused by prop trading (although it was a Bear Stearns internal hedge fund which helped to get the ball rolling). This doesn’t mean that the next one can’t be. Most would agree that reform shouldn’t seek to be solely punitive in nature nor should we engage in regulating in the rear-view mirror. It doesn’t address specific causes of the last crisis, but does address a more general, timeless, and universal one – mixing opaque risks with customer deposits.

- Just because something makes up a small percentage of a banks business or all bank business doesn’t mean it can’t present harmful risk into the system. In today’s WSJ Intelligent Investor Jason Zweig writes:

But the bad behavior on Wall Street in the 1920s wasn’t really caused by the blurring of commercial and investment banking, according to financial historian Eugene White of Rutgers University. Of the more than 7,500 banks in the U.S. in 1929, only 3% had significant securities operations. Nor did hawking investments make banks riskier for shareholders. From 1930 through 1933, nearly 2,000—or more than 26%—of federally chartered banks closed. But only about 7% of the banks that had a securities business went bust.Yes this is true, but the problem which caused the bank run in the 30’s was that some banks were holding the bag on worthless stocks. This fear grew to speculation that ALL banks had this exposure. If you remember this is similar to what happened with subprime. Everybody was asking is this bank or that bank subprime. Subprime loans were a small percentage of the total assets on the balance sheets but caused a disproportionate amount fear. Fear is a powerful emotion and if you look at the opacity surrounding some principal investments banks invest in, it isn’t hard to see this happening again. It’s best to keep risks surrounding customer’s deposits as simple and transparent as possible. While this proposal isn’t as far-reaching as Glass-Steagall was, I don’t think the original law was completely unfounded.

- This isn’t going to kill market-making as many people are claiming. One of the biggest options market maker is Citadel. Citadel is a hedge fund, not a bank. There is no law in finance that says the same place I deposit my money has to be making markets in securities. Market makers provide a valuable service to the market place – liquidity – and they get paid a spread to do so. It also helps dealers underwrite and provide capital. It is a business that is obviously viable on its own and existed before Graham-Leach-Bliley. If prop trading is something that helps facilitate market making perhaps the whole enchilada should be separated.

- Most large financial supermarkets failed, why argue against reality? Citi and Bank of America (and Wachovia) should be a referendum on Graham-Leach-Bliley. In the 1990’s, the bill was introduced in order to put the Citigroup merger through. Citigroup has failed and is still on government life support. There is nothing that has happened that convinces me that this is the model that works, so why fight to save it? To those that scream “FREE MARKETS!”, the market has spoken and it said it doesn’t like these large financial institutions. Without government intervention they would already be dead by now.

Those are some of the ideas that have been bouncing around my head the last few days. As I was writing this, The Epicurean Dealmaker shared an interesting FTAlphaville article that says how the proposal also helps crack down on some conflicts of interest on Wall Street and indirectly on pay, that is worth reflecting on as well.

I welcome comments, criticisms, and ideas. I think those looking for reform have been given a gift here, as reform is now back on the agenda. Instead of attacking the idea we in the blogosphare should be thinking more deeply, constructively criticizing, on it and improving it, because hopefully they are listening.